Top 10 facts about sepsis: technology & hospitalisation

Sepsis is known as the ‘silent killer’ and it is estimated that the inflection claims 11m lives per year – more than cancer. Although preventable and treatable, efforts to reduce the dangers of sepsis are frustrated by the fact that its symptoms often mimic common illnesses, making it difficult to recognise.

Dr. Geraldine Finlay, Senior Physician Editor for UpToDate from Wolters Kluwer Health, provides the Top 10 must-know things to look out for when diagnosing and treating sepsis.

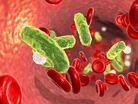

1. Sepsis: what it is

Sepsis is an infection in the bloodstream. It can result in life-threatening conditions such as extremely low blood pressure, organ failure throughout the body – commonly lung organ failure – and consequently, death.

2. The symptoms of sepsis

The symptoms of sepsis are highly variable and are dependent on the cause of the infection. The patient will experience the symptoms of the cause, and also of sepsis. The symptoms of sepsis can vary from dizziness due to low blood pressure, fever, confusion, shortness of breath, and low oxygen levels.

3. What causes sepsis?

Any infection anywhere can cause sepsis. Some common causes include skin infections, lung infections such as pneumonia, or urinary tract infections. Less common reasons for sepsis are infections in the brain like meningitis and encephalitis, tooth or belly abscess, or heart valve infections. Any and every single organ can be infected with a microorganism that can lead to sepsis. Sepsis becomes severe and life threatening when the infection moves out of the organ and starts to circulate through the bloodstream.

4. How is sepsis diagnosed?

You need a good clinical history for the patient, and a good level of suspicion. Once you suspect someone has an infection, through your clinical history and examination, clinical tests are targeted towards that. So, you might get a complete blood count (CBC) and blood tests that are representative of organ failure, like liver and kidney function tests. A chest x-ray or electrocardiogram (ECG) might also be done, and you should take blood cultures and a sample (if feasible) from the suspected infected organ, such as the urinary tract. The results for these tests can take days to come back, so sepsis is often preliminarily diagnosed and later confirmed by positive cultures. The clinician needs to have a medium to strong suspicion to start treatment, while also being mindful of overprescribing antibiotics which promotes antibiotic resistance.

5. How dangerous is sepsis?

The danger of sepsis can range from mildly dangerous to life threatening. The difficulty is that there are few accurate predictors that indicate which patients develop life threatening disease. Some patients are part of a clear risk group – such as those who are older, immune-suppressed or undergoing cancer therapy. For some, however, the severity of the condition is completely unexpected. Thus, there are also very healthy immune-competent patients who develop life-threatening symptoms of sepsis who can die as a consequence. This is why early treatment at the point when you diagnose sepsis, or suspect it, is really important. For every hour sepsis goes untreated, mortality increases by about 8%.

6. Early sepsis diagnosis increases the chance of recovery

Early diagnosis often means early treatment, which increases chances of recovering, as sepsis is unpredictable in its severity. Most of the time, treatment will already start for sepsis even if it is still under suspicion, because it might be too late otherwise.

7. The sepsis prognosis

With sepsis it is extremely difficult to predict how the condition will develop. Whether the patient is in a risk group or not can give some indication of how severe the symptoms might get and thus whether it may become life threatening. The stage at which the condition is diagnosed, and treatment is started can also give an indication of how dangerous sepsis might become. We do know that early detection and early treatment leads to better outcomes and the less likely that complications or death will occur.

8. The treatment for sepsis

Fluids, antibiotics, and source control (removing or treating the source of infection, such as an abscess) are the cornerstone of sepsis treatment. The treatment starts preferably in the first and definitely within the first three hours following a suspected diagnosis. As fluids are more readily available, these are often the first thing administered to the patient followed by antibiotics targeted at the suspected organism. Administered antibiotics should be broad in their coverage and can be narrowed once the organism is identified at a later date.

9. Who is at risk of sepsis?

Older patients (> 65 years) and patients who are immune-supressed have a higher likelihood of developing life-threatening sepsis. Other risk factors include recent intensive care unit admission, diabetes, obesity, cancer, pneumonia, and previous recent hospitalisation. There may also be a genetic predisposition to developing sepsis.

10. How can technologies, like clinical decision support, help to tackle sepsis?

Clinical decision support (CDS) systems, like UpToDate, provide guidance for clinicians treating sepsis. CDS can help identify suspected sepsis early and alert the clinicians. Electronic health records (EHRs) can send automated ‘early alerts’ when a patient’s test results and vital signs suggest sepsis. Real-time interactive sepsis surveillance tools, like POC Advisor, analyse a broad range of EHR data to provide early-warning alerts of patients at risk. Artificial intelligence tools, such as Natural Language Processing (NLP), are used to speed this process even more. NLP can extract meaningful clinical information from free-text narratives (progress notes, radiology reports, and more) and provide the information to POC Advisor’s decision support algorithms. These clinically maintained algorithms refine alert accuracy and reduce false positives for conditions resembling sepsis signs. As CDS becomes more sophisticated, these technologies can further help with early fluid management (e.g., type and rate of fluids), antibiotic selection, and prompt consideration of infection source control.